The morning of 2 FEB 1972 dawned cool and bright in central Thailand. After a light breakfast at the chow hall I walked the five blocks to work at Detachment 17, 601st photo Flight at Korat RTAFB.

I was more than a little excited this day as I was scheduled to fly on my first ever EB-66 mission as a combat photographer, escorting B-52s on a raid over North Vietnam. I got to the photo lab early to get my gear and test all the equipment I would be taking along. Take-off was scheduled for sometime around 1100 hrs.

Around 930 hrs, as I was leaving to head over to the personal equipment section to retrieve my helmet, survival vest and .38 revolver, a call came in to the lab that a photographer would be needed immediately as an F-105 (No. 63-8284) had just exploded on take-off!

I obviously couldn’t go so another photographer went on the assignment. I proceeded to get my personal equipment and go on to the pre-flight briefing at 42nd TEWS HQ at the opposite end of the runway. Today we would be escorting 2 “cells” of B-52s from Utapao into North Vietnam.

By the time the briefing was over and we all began making our way out to the aircraft, the air was beginning to get very hot. The EB-66E with SEA camouflage paint scheme just sat there soaking up the heat from that burning Thai sun. When we arrived, the ground crew had just shoved the air-conditioning hoses into the crew cabin and as I squeezed aboard I began to feel the sweat run down my legs. Finally, after a few minutes, the air-conditioning slowly began to overcome the oppressive cabin heat. As I got myself situated on the left side of the aircraft, in what was known as the “gunners seat”, I noted what a horribly small window I had to shoot out of and wondered to myself I could possibly get any images at all ! But hell, I was going and I was determined to try!

With the rest of the crew aboard, the aircraft was buttoned up and the engines began turning. Irreverently referred to as “whining pigs”, the EB-66s were known for their loudness and high pitch of their engines. As the pilot advanced the throttles we screamed our way out of the revetment area. Passing by, I noted the ground crew, some with their “ear muffs” on and others with their hands over their ears to dull the shrieking engines. Slowly we trundled down the taxiway and out onto the run-up area where the final pre-flight checks were completed.

We began our take-off roll in the unusual west to east direction. This was because they did not want us to overfly the F-105 accident scene at the western end of the runway while crews were working to clear the debris. As max power was applied, the plane began to accelerate rapidly and I watched out my tiny window as the foot markers alongside the runway flashed by.

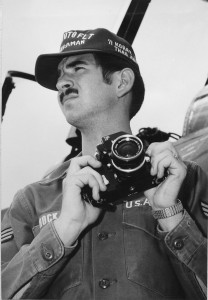

Ground crew clean and ready an EB-66 for another jamming mission over North Vietnam. This particular aircraft was destroyed in combat and became well known from a movie made about the escape of the navigator, Lt.Col. Iceal Hambleton. The movie was "Bat 21" starring Danny Glover and Gene Hackman. Sadly, all other crew members were lost that day as were a number of other crews assisting in the rescue. Sgt. James H. Alley, a motion picture photographer, was on board the ill-fated HH-53 "Jolly 67" that participated in the rescue attempt and subsequently crashed due to ground fire in Quang Tri Province.

Suddenly .. at the point of no return, the pilot called over the interphone that he was aborting the takoff! The press of acceleration quickly reversed and now our chest straps held us in our seats. I could not see directly forward because a bulkhead and the pilot were right in front of me. But by leaning over to the right I could look past the pilot and see out the windscreen and what I saw was the end of the runway and and a big cyclone fence rushing at us at an alarming rate! The pilot was making every effort to brake his unruly steed and at last I could feel us slowing and in a few more long seconds we were finally stopped, just short of the end of the runway. I think I could have thrown a rock and hit that cyclone fence!

Whew … that was close!

We taxied back to 42nd TEWS where the “spare” aircraft was waiting. As we left this plane, an EB-66E, I learned that the spare was an EB-66C ( No. 54-0540) and it did not have a “gunner” seat installed. That meant I would be staying behind.

By this time it was about noon. I knew at some point aerial photos would have to be taken of the F-105 crash site. Rather than return to the Photo Lab, I called MSgt. Skelton T. Duggar, NCOIC of the Photo Lab, to see what was needed. He told me to go to the operations building for the HH-43 Kaman helicopter crews and await further instructions.

A short walking distance away, I went there and spoke to the Operations Officer, told him why I was there and he said they had not received any tasking for aerial photography. I had never seen an Kaman HH-43 “Huskie” close up before so I went outside to wait and look over the unusual aircraft. As I stood there, the “spare” EB-66C, with one less crewmember, screamed past. I was more than a little disappointed.

The runway at Korat RTAFB is well over 6,000 feet long and has a rather pronounced “hump” in it. It was impossible to see from one end of it to the other. When an aircraft took off it was out of sight for a few seconds as it went over the hump until it actually became airborne.

That day, EB-66C (No. 54-0540) became airborne for only a few short seconds. As it cleared the runway, power and control was lost and the aircraft crashed, wheels up, into the overrun area at the west end of the Korat runway. Its’ engine nacelles acting as giant scoops, scraping up grass and stones, sucking them into the engines. The aircraft came to rest on its’ belly with the engines acting like outriggers, holding it upright. ( By this time most of the F-105 crash had been mostly cleaned up.) Luckily, all 6 crew members escaped the crash unharmed.

We soon got the word at Heli Ops that the EB-66 had crashed and that all aircraft were grounded, including the helicopter. Fuel contamination or sabotage was suspected and had to be checked out. An hour passed and we were cleared to fly.

The mission to photograph the crash sites was on and we flew down the runway and made a few orbits of the resting place of the EB-66 as well as the overrun strip where parts of the F-105 still lay. All the while I was clicking away with my trusty Nikon FTn. We continued out over the base perimeter to the west about a half mile off the base to where the compressor phase and main part of the F-105 engine had impacted. Remarkably, it had just missed a guard tower at the edge of the base and continued out over a Thai civilian highway. Fortunately, it landed in an empty field, gouging a long, deep furrow.

The chopper returned to its’ pad and I hitched a ride back to the photo lab.

What a morning, what a day! But I wasn’t done yet. Returning to the lab, the Safety Officer was there needing a photographer to go out to the EB-66 crash site for ground level crash photos, so I went with him for a firsthand look at the damage to the aircraft that I was “almost” on. It was really messed up and never flew again.

Returning to the photo lab once again, I set about putting away my equipment as it was getting late in the day. I hadn’t eaten since early morning and I was looking forward to chow!

Suddenly, the phone rang … ring, ring, …ring, ring,

MSgt. Duggar called out from his office … “Any photographers here … “? “Yes, Sgt. Duggar, Hock’s here”, I yelled. “Grab a camera, somebody will be coming right over to pick you up!”.

Great! Just what I needed. “Where the hell is everybody” I wondered. “Am I the only guy here”? Within minutes the Mortuary Officer arrived. We went out, jumped in his jeep and sped off. As we rolled down the flight line I asked what I was to shoot. “A body”, he quietly replied.

Now I’ve never been big on seeing gore so I asked him to elaborate on what I was going to see. I wanted to prepare myself for the job ahead. A knot formed in my stomach. He told me it was the pilot fatality from the F-105 accident and that he merely appeared to be sleeping. Entering the rather dim, refrigerated container that served as our morgue, I found my subject still clothed in his flight suit, laying flat in a dignified way, and from all appearances, simply sleeping. I took my photos in the most respectful way I possibly could under the direction of the Mortuary Officer and left the container a bit more solemn than I was a few hours earlier. It was one thing to hear about “combat losses”, they are just words … but to see them up close and personal was quite another matter.

The thought crossed my mind that I could have been in the refrigerator that day too. It just wasn’t my turn. It was a sobering thought for a young man barely age 21.

For me, this singular event finally put a human face on the Vietnam War. From then on I tended to think of the conflict in much more human terms. When we “lost a plane”, it wasn’t just the plane anymore. It was the crew of the plane we lost.

It made a big difference …

Epilog :

As No. 54-0540 cleared the runway one of my fellow 601st photographers was busy at the southwest end of the runway documenting the debris and parts of the disintegrated F-105 aircraft (No. 63-8284) for the Accident Investigation Board.

Hearing the EB-66s’ engine whine begin to diminish, he looked up and saw the aircraft begin to sink, strike the ground and careen forward out of control in a huge cloud of dust, grinding to a halt in the overrun area. His immediate thought was of the crew and, disregarding his own safety, he rushed towards the aircraft. In his haste to help, he tripped and fell on the uneven ground and was knocked unconscious and he himself had to be taken to the base hospital.

When I returned to the photo lab after taking the aerial photos of the crash sites, I headed directly to the break room to get myself a cold drink. As I entered the room I saw the crash photographer was there, his 1505 uniform soiled and smudged .. covered with gray ash from falling into the jet fuel burned grassy area next to the runway. He was staring at the floor. He looked up at me for a second, recognized me, then leaped out of his chair and rushed over and threw his arms around me. “I thought you were in that god-damned plane” he said quietly, nearly in tears.

I was totally taken aback because at that point I knew nothing about what had happened to him out along the runway. As we talked I learned all that had happened to him that day. I could not help but be touched and humbled by the care and sincere concern expressed by this young man that I hardly even knew.

Thank you Sgt. XXX, …. I’ll never forget it.

(I’ve withheld the name of this individual to prevent him any embarrassment. He and I know who he is and that all that really matters.) -MPJ-

Editors Note: It really was quite a day and a story that needed documenting. There are many more great stories I’m sure. And I hope others will be inspired to tell of their experiences and post some of their own historical, here to for unseen photos languishing in their closets. – Steve Hock